Bicycle and motorcycle geometry

Bicycle and motorcycle geometry is the collection of key measurements (lengths and angles) that define a particular bike configuration. Primary among these are wheelbase, steering axis angle, fork offset, and trail. These parameters have a major influence on how a bike handles.

Contents |

Wheelbase

Wheelbase is the horizontal distance between the centers (or the ground contact points) of the front and rear wheels. Wheelbase is a function of rear frame length, steering axis angle, and fork offset. It is similar to the term wheelbase used for automobiles and trains.

Wheelbase has a major influence on the longitudinal stability of a bike, along with the height of the center of mass of the combined bike and rider. Short bikes are much more likely to perform wheelies and stoppies.

Steering axis angle

The steering axis angle, also called caster angle, is the angle that the steering axis makes with the horizontal or vertical, depending on convention. The steering axis is the axis about which the steering mechanism (fork, handlebars, front wheel, etc.) pivots. The steering axis angle usually matches the angle of the head tube.

In bicycles, the steering axis angle is called the head angle and is measured clock-wise from the horizontal when viewed from the right side. A 90° head angle would be vertical. For example, Lemond[1] offers:

- a 2007 Filmore, designed for the track, with a head angle that varies from 72.5° to 74° depending on frame size

- a 2006 Tete de Course, designed for road racing, with a head angle that varies from 71.25° to 74°, depending on frame size.

In motorcycles, the steering axis angle is called the rake and is measured counter-clock-wise from the vertical when viewed from the right side. A 0° rake would be vertical. For example, Moto Guzzi[2] offers:

- a 2007 Breva V 1100 with a rake of 25°30’ (25.5 degrees)

- a 2007 Nevada Classic 750 with a rake of 27.5° (27.5 degrees)

Fork offset

The fork offset is the perpendicular distance from the steering axis to the center of the front wheel.

In bicycles, fork offset is also called fork rake. Road racing bicycle forks have an offset of 40-45mm.[3]

Required rake angle arose from early times when lightweight bicycles suffered fork failures from road shock. Most fatigue failures of forks result in a fork blade breaking at the rear edge of the fork crown from repeated vertical road shocks. Before most roads were paved, fork rake had a lower angle so the fork would be loaded axially on rougher surfaces. As most roads became paved, bicycles forks were made steeper, which also gave lighter steering.

In motorcycles with telescopic fork tubes, fork offset can be implemented by either an offset in the triple tree, adding a rake angle (usually measured in degrees from 0) to the fork tubes as they mount into the triple tree, or a combination of the two.[4] Other, less-common motorcycle forks, such as trailing link or leading link forks, can implement offset by the length of link arms.

Fork length

The length of a fork is measured parallel to the steer tube from the lower fork crown bearing to the axle center.[5]

Trail

Trail, or caster, is the horizontal distance from where the steering axis intersects the ground to where the front wheel touches the ground. The measurement is considered positive if the front wheel ground contact point is behind (towards the rear of the bike) the steering axis intersection with the ground. Most bikes have positive trail, though a few, such as the two-mass-skate bicycle and the Python Lowracer have negative trail.[6]

Trail is often cited as an important determinant of bicycle handling characteristics, such as here[7] and here,[8] and is sometimes listed in bicycle manufacturers' geometry data, although Wilson and Papodopoulos argue that mechanical trail may be a more important and informative variable.

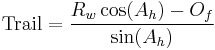

Trail is a function of head angle, fork offset or rake, and wheel size. Their relationship can be described by this formula:[9]

where  wheel radius,

wheel radius,  is the head angle measured clock-wise from the horizontal and

is the head angle measured clock-wise from the horizontal and  is the fork offset or rake. Trail can be increased by increasing the wheel size, decreasing or slackening the head angle, or decreasing the fork rake or offset. Trail decreases as head angle increases (becomes steeper), as fork offset increases, or as wheel diameter decreases.

is the fork offset or rake. Trail can be increased by increasing the wheel size, decreasing or slackening the head angle, or decreasing the fork rake or offset. Trail decreases as head angle increases (becomes steeper), as fork offset increases, or as wheel diameter decreases.

Motorcyclists tend to speak of trail in relation to rake angle. The larger the rake angle the larger the trail. Note that, on a bicycle, as rake angle increases, head angle decreases.

Trail can vary as the bike leans or steers. In the case of traditional geometry, trail decreases (and wheelbase increases if measuring distance between ground contact points and not hubs) as the bike leans and steers in the direction of the lean.[10] Trail can also vary as the suspension activates, in response to braking for example. As telescopic forks compress due to load transfer during braking, the trail and the wheelbase both decrease.[11] At least one motorcycle, the MotoCzysz C1, has a fork with adjustable trail, from 89 mm to 101 mm.[12]

Mechanical trail

Mechanical trail is the perpendicular distance between the steering axis and the point of contact between the front wheel and the ground. It may also be referred to as normal trail.[10]

Although the scientific understanding of bicycle steering remains incomplete,[13] mechanical trail is certainly one of the most important variables in determining the handling characteristics of a bicycle. A higher mechanical trail is known to make a bicycle easier to ride "no hands" and thus more subjectively stable, but skilled and alert riders may have more path control if the mechanical trail is lower.[14]

Wheel flop

Wheel flop refers to steering behavior in which a bicycle or motorcycle tends to turn more than expected due to the front wheel "flopping" over when the handlebars are rotated. Wheel flop is caused by the lowering of the front end of a bicycle or motorcycle as the handlebars are rotated away from the "straight ahead" position. This lowering phenomenon occurs according to the following equation:

- f = b sin ∂ cos ∂[15]

where:

- f = "wheel flop factor," the distance that the center of the front wheel axle is lowered when the handlebars are rotated from the straight ahead position to a position 90 degrees away from straight ahead

- b = trail

- ∂ = head angle

Because wheel flop involves the lowering of the front end of a bicycle or motorcycle, the force due to gravity will tend to cause handlebar rotation to continue with increasing rotational velocity and without additional rider input on the handlebars. Once the handlebars are turned, the rider needs to apply torque to the handlebars to bring them back to the straight ahead position and bring the front end of the bicycle or motorcycle back up to the original height.[16] The rotational inertia of the front wheel will lessen the severity of the wheel flop effect because it results in opposing torque being required to initiate or accelerate changing the direction of the front wheel.

According to the equation listed above, increasing the trail and/or decreasing the head angle will increase the wheel flop factor on a bicycle or motorcycle, which will increase the torque required to bring the handlebars back to the straight ahead position and increase the vehicle's tendency to veer suddenly off the line of a curve. Also, increasing the weight born by the front wheel of the vehicle, either by increasing the mass of the vehicle, rider and cargo or by changing the weight ratio to shift the center of mass forward, will increase the severity of the wheel flop effect. Increasing the rotational inertia of the front wheel by increasing the speed of the vehicle and the rotational speed of the wheel will tend to counter the wheel flop effect.

A certain amount of wheel flop is generally considered to be desirable. In the magazine Bicycle Quarterly, bicycle dynamics expert Jan Heine wrote, "A bike with too little wheel flop will be sluggish in its reactions to handlebar inputs. A bike with too much wheel flop will tend to veer off its line at low and moderate speeds."[15]

Modifications

Forks may be modified or replaced, thereby altering the geometry of the bike.

Changing fork length

Increasing the length of the fork, for example by switch from rigid to suspension, raises the front of the bike and decreases the head angle. [5]

A rule of thumb is a 10mm change in fork length gives a half degree change in the head angle.

Changing fork offset

Increasing the offset of a fork reduces the trail, and if performed on an existing fork without lengthening the blades, shortens the fork. [17]

Legal requirements

The state of North Dakota (USA) actually has minimum and maximum requirements on rake and trail for "manufacture, sale, and safe operation of a motorcycle upon public highways."[18]

"4. All motorcycles, except three-wheel motorcycles, must meet the following specifications in relationship to front wheel geometry:

- MAXIMUM: Rake: 45 degrees - Trail: 14 inches [35.56 centimeters] positive

- MINIMUM: Rake: 20 degrees - Trail: 2 inches [5.08 centimeters] positive

Manufacturer's specifications must include the specific rake and trail for each motorcycle or class of motorcycles and the terms "rake" and "trail" must be defined by the director by rules adopted pursuant to chapter 28-32."

Other aspects

For other aspects of geometry, such as ergonomics or intended use, see the Bicycle frame article. For motorcycles the other main geometric parameters are seat height and relative foot peg and handlebar placement.

See also

References

- ^ "Lemond Racing Cycles". 2006. http://www.lemondbikes.com/. Retrieved 2006-08-08.

- ^ "Moto Guzzi USA". 2006. http://www.motoguzzi-us.com. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ "Geometry of Bike Handling". Calfee Design. http://www.calfeedesign.com/tech-papers/geometry-of-bike-handling/. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- ^ Hornsby, Andy (2006). "Back to School". http://www.american-v.co.uk/technical/handling/geometry/body.html. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ a b Rinard, Damon (1996). "Fork Lengths". http://www.sheldonbrown.com/rinard/forklengths.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Frame Geometry". http://www.python-lowracer.de/geometry.html. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- ^ Josh Putnam. "Steering Geometry: What is Trail?". http://www.phred.org/~josh/bike/trail.html. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- ^ "An Introduction to Bicycle Geometry and Handling.". C.h.u.n.k. 666. http://www.dclxvi.org/chunk/tech/trail/. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- ^ Putnam, Josh (2006). "Steering Geometry: What is Trail?". http://www.phred.org/~josh/bike/trail.html. Retrieved 2006-08-08.

- ^ a b Cossalter, Vittore (2006). "THE TRAIL". Archived from the original on 2007-02-16. http://web.archive.org/web/20070216080619/http://www.dinamoto.it/DINAMOTO/on-line+papers/Avancorsa/trail.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ Cossalter, Vittore (2006). Motorcycle Dynamics (Second Edition ed.). Lulu.com. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-4303-0861-4.

- ^ "MotoCzysz". 2006. http://www.motoczysz.com/main.php?area=bike. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ Whitt, Frank R.; Jim Papadopoulos (1982). "Chapter 8". Bicycling Science (Third edition ed.). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Watkins, Gregory K.. "The Dynamic Stability of a Fully Faired Single Track Human Powered Vehicle". Archived from the original on 2006-07-17. http://web.archive.org/web/20060717170926/http://www.coe.uncc.edu/~gkwatkin/Dissertation/chapter14.pdf. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ a b Heine, Jan. "Bicycle Quarterly -- Glossary". Vintage Bicycle Press. http://www.vintagebicyclepress.com/glossary.html. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ Foale, Tony (2002). Motorcycle Handling and Chassis Design. Tony Foale Designs. pp. 3–11. ISBN 8493328618. http://www.tonyfoale.com/book/. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ Matchak, Tom (2006). "Fork Re-Raking and Head Angle Change". http://www.phred.org/~alex/bikes/Fork%20Re-raking%20Summary.pdf. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ "CHAPTER 39-27 MOTORCYCLE EQUIPMENT". 2006. http://www.legis.nd.gov/cencode/t39c27.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-14.